The 20 Billion Cold War Survival Biscuits that Were Never Baked

By Alicia Bones

About those reader’s poll results! You’re a bunch of highly literate non-partiers who eat and cook and enjoy both comedy and cultural history podcasts. Your favorite social media accounts are all over the place and a lot of you watch “The Bear” - I should probably finally check it out. One of you said your favorite food show is “Bob’s Burgers.” That person gets it. Truly, thank you to everyone who completed the survey, and another thanks to the people who listed me as a useful food resource. It means a lot! Now please enjoy this story by Alicia Bones. It’s fascinating. —Katherine

The 20 Billion Cold War Survival Biscuits that Were Never Baked

by Alicia Bones

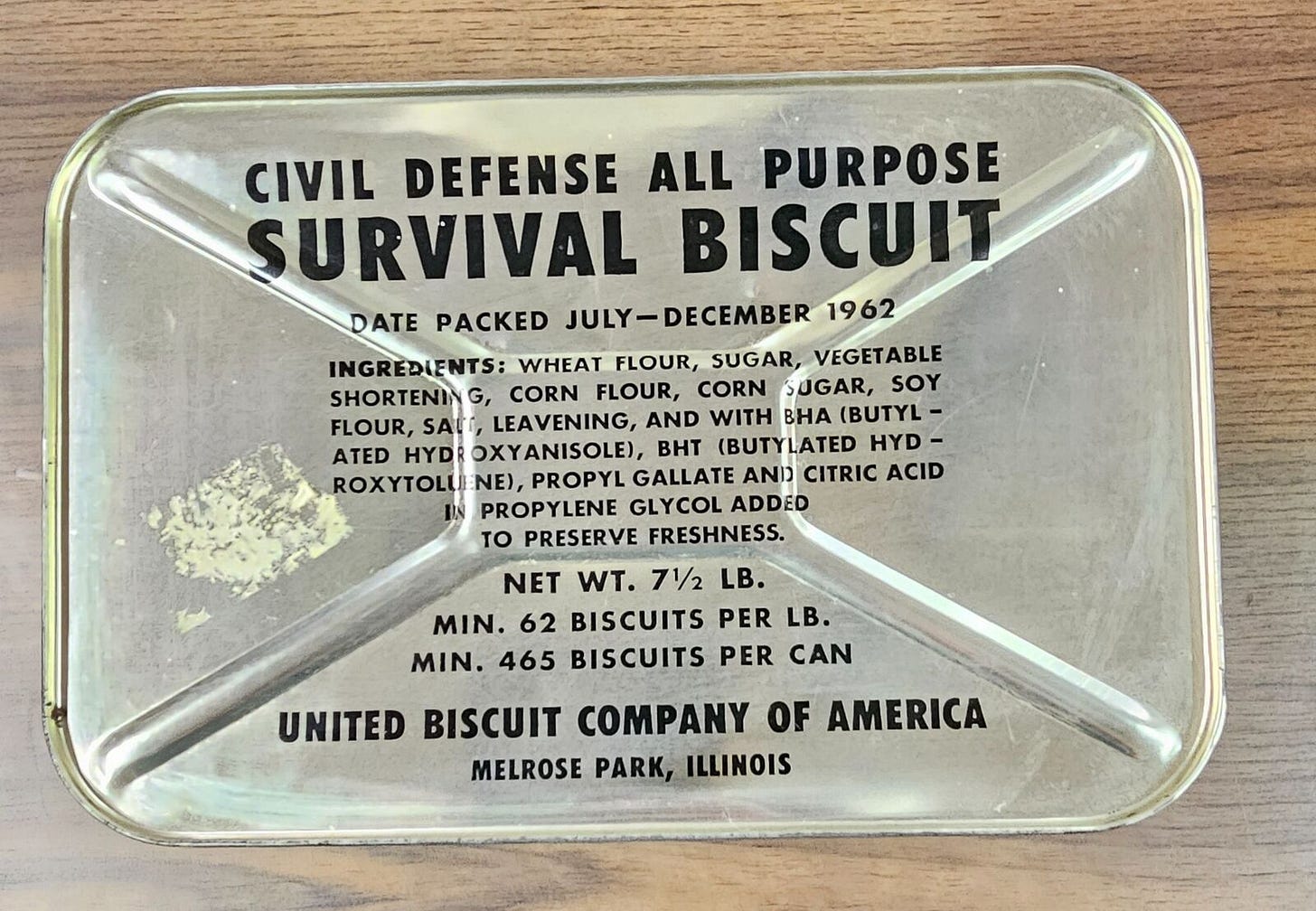

In 2017, a Massachusetts city hall was overrun with millions of drugstore beetles. When a pest control company was called to the building, they discovered the source: rotting civil defense crackers. Since the early 1960s, the crackers had been stored in aluminum cans in an underground bunker beneath city hall. Over the decades, leaks had caused the aluminum to crack open and the crackers to rot, attracting the insects.

These crackers, designed to help those lucky enough to make it to bunkers after atomic blasts, were part of the government's attempt to stock federally-designed bunkers with enough highly-engineered, tasteless wheat crackers for "shelterees" to survive for two weeks underground.

To add rations to public fallout shelters in the early 1960s, John F. Kennedy's government worked with national cracker manufacturers with a goal of producing more than 20 billion crackers to be distributed to more than 240 million public and private shelters. But only 165,000 tons of crackers were ever baked, and the most generous estimates report that only about a third of public fallout shelters were stocked.

Why did the federal government expend so much money and effort to identify and stock public fallout shelters, only to have the effort fail?

Backyard Fallout Shelters

From the late 1940s on, Americans were told that they should prepare for nuclear war by building shelters in their basements or backyards to wait out the fallout from atomic bombs. But by the early 1960s, there was still no federal program for identifying, labeling, and equipping shelters.

One of the drivers of this private-bunkers-only mentality was capitalism. Under threat of conflict, socialist- and socialist-leaning countries and regions like the Soviet Union and Scandinavia built public fallout shelters en masse. But in capitalist countries like the United States and the U.K., "bunkers were built for politicians, for elites, for wealthy people in positions of power. There was very little provision made for the general public," Bradley Garrett, author of the book “Bunker: What It Takes to Survive the Apocalypse,” told Newsweek.

Though the government wasn't building bunkers, private citizens weren't frantically installing them either. In 1961, Gallup found that only 7% of Americans planned to build shelters. Americans believed that nuclear war was a real possibility, but they didn't construct private shelters for several reasons, including price, effectiveness, the morality of excluding neighbors who didn't have their own shelters, and fears about quality of life after nuclear war.

When Kennedy first took office in 1961, he asked LIFE magazine to send a letter to subscribers encouraging them to construct their own fallout shelters. But he quickly recognized that many poor and urban citizens couldn't build their own bunkers or use their neighbors’, especially after an article in Time described a man who promised to mount a machine gun on his fallout shelter to keep his neighbors out.

So, JFK decided to de-emphasize the government's emphasis on private shelters and established the National Fallout Shelter Survey and Marking Program to develop bunkers for the public.

National Fallout Shelter Program

By 1962, when the program began, it wasn't that Americans thought nuclear war wouldn't happen, but that shelters wouldn't help if it did. For all the runs on grocery stores during the Cuban Missile Crisis, many Americans were desensitized to the threat. Historian Sarah E. Robey explained:

"[F]ederal planning recommendations — first for public bomb shelters, then urban evacuation, then private fallout shelters — had changed several times over the course of the 1950s. To observers, these plans never seemed to keep pace with rapidly-advancing nuclear weapons technology, which became more and more destructive with each passing year."

Still, the federal government pressed on with the National Fallout Shelter program. Kennedy was determined to identify and stock bunkers for 50 million Americans, extolling a hopeful statistic that a combination of private and public shelters would help 97% of Americans survive nuclear war. He requested $207 million ($1.7 billion today) from Congress, with the goal of developing 240 million well-stocked shelter spaces by 1968.

In the program's first year, nearly 104 million shelter spaces were identified nationwide, typically basements in office and municipal buildings. In New York, "38 architectural firms inspect[ed] 105,244 large buildings. Eventually, some 19,000 of them would become shelters." In 1962, the first fall-out shelter signs were rolled out in 14 cities. The still well-known shelter signs were yellow, black, and reflective, so they could be seen by the light of cigarette lighters.

But these auspicious beginnings didn't lead to success. Many shelters leaked or were overrun by rats, while others never were stocked with rations, water, or medical supplies. And many Americans figured that even if they were lucky enough to arrive at a bunker within 15 minutes of a blast, they might find that the bomb had destroyed the entryway.

As Robert Klara notes, citizens also worried they'd be "barbecued" underground.

"The shelters’ dubious utility also hinged on the shaky bet that the Soviets would drop only one bomb on a city like New York, an assumption that Khrushchev himself later ridiculed in his memoirs," he says.

For the most part, fallout shelters promised a security that many Americans found doubtful in the face of nuclear war.

Food in Fallout Shelters

Still, the government soldiered on. Even by its own account, citizens in their own fallout shelters would eat better than those in public bunkers. A 1961 government-issued pamphlet advised families to fill their bunkers with familiar foods that were "more heartening and acceptable during times of stress." People created shelter pantries filled with canned vegetables, beans, Tang, canned tuna, peanut butter, and cereal.

Americans who would be at work or in public when a bomb hit wouldn't be so gastronomically lucky. From the late 1950s on, the federal government was hunting for a nutritious "Doomsday food" that could be mass-produced and easy to store. It spent millions to identify bulgur wheat as the cornerstone of post-apocalyptic cuisine, primarily because, according to deputy assistant secretary of defense for civil defense Paul Visher, "its shelf life has been established by being edible after 3,000 years in an Egyptian pyramid."

The official plan was to make 150 million pounds of crackers using three million bushels of bulgur wheat. In 1961, the government signed contracts with some of the biggest grain manufacturing plants in the country, including Kroger, Nabisco, and the United Biscuit Company of America (now Keebler). Shelterees were advised to eat six 125-calorie crackers per day at various intervals, perhaps to pass the time in a dank bunker. The shelf life of these crackers was about five years.

The feds also developed carbohydrate supplement candies. A cheerful alternative to the chalky-tasting and saltless crackers, these hard candies were colored yellow and red.

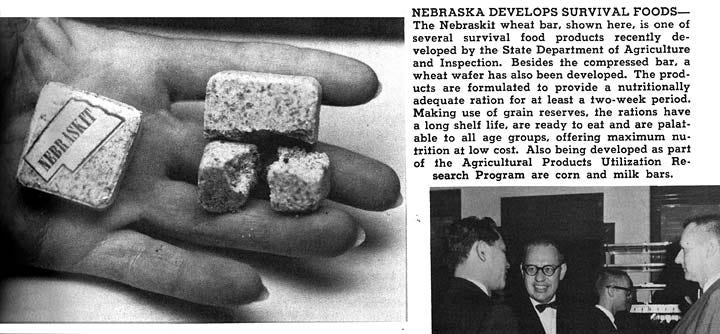

State governments also got into the act. For instance, Nebraska created its own crackers, dubbed "Nebraskits." According to a contemporary news feature, these were "deliberately tasteless" because "any sweetness or flavor quickly becomes intolerable" when eaten repeatedly. Surpassing the federal government's rations, Nebraskits would provide 900 daily calories in the form of 36 crackers.

Companies without contracts also developed fallout foods. General Mills created a granulated protein mix called Multi-Purpose Food that could be served hot or cold. The company recommended three scoops per day, but it was a little more taste-conscious than the creators of Nebraskits, who suggested diners add the powder to tomato juice or peanut butter sandwiches.

Whether or not Americans would have remained for two weeks in shelters with food this dismal was questionable. In a test run of what it would be like to stay in a fallout shelter for 14 days, the Navy experimented with a survival cracker diet for 100 sailors in 1962. However, the agency wouldn't serve them only the government-issued crackers, instead supplementing the dry wafers with coffee, soup, peanut butter, and jellies.

Either because of , or despite, the rush to create shelter foods, the rollout was not a success. Many crackers were never shipped and rotted in warehouses. Estimates now vary about how many shelters were actually stocked. Some suggest fewer than 10% of shelters ever saw supplies, while others say a third received their rations. Others suggest 100,000 fallout shelters were stocked with food and supplies during the eight years of the program, from 1962 to 1970.

The Fallout of Fallout Shelters

Luckily for many, these cracker rations and Multi-Purpose Food remained, for the most part, uneaten. By 1963, Russia and the United States signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty, signaling the death knell for support of continued underground bunker development. Still, the feds officially stocked and maintained shelters for seven more years, until 1970.

What happened to all of the uneaten crackers? By the early 1970s, the crackers that had been baked had long exceeded their shelf lives, but there were still some 150,000 tons remaining in storage. The Office of Civil Defense decided to use them, sending boxes to victims of the 1974 Bangladesh monsoon and then, in 1976, to earthquake-damaged Guatemala, where those who consumed them faced “severe gastric disturbances.”

Over the years, many shelters, like the one in Massachusetts, have been forgotten. Recently, though, an interest in fallout bunkers has reemerged. Some people are again preparing for climate change and other disasters by developing private shelters across the country.

Like in the days before the government fallout shelter program, however, only the well-off can afford them. For instance, the Survival Condo is a 15-story luxury underground bunker in Kansas in a missile silo. Prices start at $1,500,000 for a half-floor unit stocked with five years of food supplies. There is no official estimate of how many private bunkers are in the United States; Garrett said it is "safe to say" that there are millions of them.

These bunkers won't be stocked with barely-edible crackers, either. Elites will ride out the apocalypse eating well. Today, survival rations are marketed to anti-establishment “preppers” who plan to eat well after doomsday. Think televangelist Jim Bakker’s survival food tagline: “Imagine — the world is dying and you’re having a breakfast for kings” and the Glenn Beck-backed My Patriot Supply’s mac & cheese, potato soup, and orange energy drinks.

The rest of us might wonder where these public bunkers might be if we ever need to survive a future disaster. Many locations are lost to time. But as the Massachusetts pest control company discovered, you never know when a new/old one might be discovered. As workers threw away bushels of beetles, cardboard, and trash into 13 dumpsters, they found four other bunkers blocked by walls of crumbling, rotten crackers.

Tyromancy with Jennifer Billock

There's no end of ways to tell the future. But most importantly: with cheese.

Listen to Smart Mouth: iTunes • Google Podcasts • Pandora • Spotify • RadioPublic • TuneIn • Libsyn • Amazon Music

Check out all our episodes so far here. If you like, pledge a buck or two on Patreon. If you'd rather make a one-time gift, I'm on Venmo and PayPal.

If you liked the newsletter today, please forward it to someone who’d enjoy it, and tap the heart icon above or below, which will help me reach more readers. I appreciate your help, y’all!

Please note: Smart Mouth is not accepting pitches at this time.

This newsletter is edited by Katherine Spiers, host of the podcast Smart Mouth.

A TableCakes Production.

Many public schools like mine (Laurelhurst Elementary) had the iconic yellow and black Fallout Shelter sign posted at the entrances. Supposedly we would all be shepherded into the basement boiler room (oil furnaces heated water that was piped about the building and into cast-iron radiators for heat).

If we all stayed in the boiler room fallout shelter for about 2 weeks (eating wheat crackers?) we would supposedly avoid inhaling the radioactive iodine in nuclear fallout (assuming the building survived any direct blast damage).

Those days were far behind us due to nuclear detente and the 1963 nuclear test ban treaty. Hopefully political leaders of our day will share the historical concern and preclude the need to dust off all the fallout shelter signs - if not, it’s time to start stocking up on wheat crackers and potassium iodine tablets...