Please forward to a food-loving friend!

Restaurant delivery has gotten to an absurd place, what with all the apps. Here’s an NPR piece that does a great job outlining how it all works - including the rising number of “restaurants” that, by design, have addresses and kitchens but no on-site customers. I want to know: do you order delivery? Do you have a preferred app (or maybe you eschew the apps altogether)? Talk about it in the thread here.

This will be the only newsletter in December, as I’ll be attempting to take an honest, old-fashioned break from work. It’s been maybe 15 years since I’ve done it. Fingers crossed. A lot of you will be poppin’ bottles over the next few weeks, so here’s an episode all about the history of champagne: listen, then drop little bits of wine-related trivia at the next gathering.

Photo: Lachlan Hardy/Flickr

Making Manti Across the Globe

By Anna Roach

Served floating in a boiling broth or dry in a snack bowl, accompanied by garlicky yoghurt, tangy tomato sauce, or eaten all on its own: Manti, a small meat dumpling that is a staple of Armenian cuisine, arrives at the table in many forms. Diasporan Armenians, be they in Los Angeles, Boston, Montreal or Paris, brought it with them when they fled genocide in the late 1910s. It is a tangible tie to some sort of back home, to a culture they may never have known first-hand yet still live in, thousands of miles away.

Making manti is a laborious process. Dough-making is one of those skills that only tatiks, grandmothers, really seem to have mastered. The meat filling is a combination of ground meat, traditionally lamb, and any combination of garlic, parsley, onion, salt, and pepper, and usually, additional spices. Then comes the most important part, where the dough is cut into squares and the manti are shaped. This must be done carefully, and lovingly: the sides of the dough must be pinched together so as to form the shape of a little gondola, but the meat-to-dough ratio must be just right so as to fill the pastry without ripping it.

Photo: « R☼Wεnα »/Flickr

Manti are not to be eaten alone, and they are not to be made alone. In many families, they’re for celebrating special occasions: It’s a popular birthday dish. The celebration is not just the eating - it is the making. It is the garlicky smell coming from the oven. The tomato sauce stewing on the stove. The families - often the women in the families - sitting at the kitchen table, forming a manti assembly line. It’s a tradition that becomes a skill. By the time you’re grown up, you make manti the way your mother made manti, which is the way your grandmother made manti, who made manti like her mother did before her. It’s a dish that, for the most passionate manti-eaters, encapsulates history.

They’re not wrong. The origins of manti are widely disputed, perhaps partly because they are not as common in modern-day Armenia as one might expect. Today’s Armenian cuisine is very different from the cuisine that people brought with them when they left the historical Western Armenia, the parts of eastern Turkey that many Armenians were forced to leave. Soon after, the country of Armenia became a part of the Soviet Union, which famously homogenized a lot of regional foods. So, like a lot of Armenia’s most traditional dishes, manti is made more in the diasporas than it is in Armenia itself.

Where did the dish originate? Some point to the Mongol empire, others point to nomadic Turkic peoples; the only thing that is certain is that there is a manti trail that can be followed along the Silk Road. In Kazakhstan, they are steamed, and roughly the size of your palm. In Uzbekistan, they don’t even need to have meat; they’re more often made of cabbage, potato, or pumpkin. But for Armenians, not all manti are created equal: the true manti are crispy, and come on a round platter, arranged in a circular pattern. But ultimately, the historical origin of the dish matters less than the origin of one’s grandmother’s recipe: Those manti, made from a recipe scrawled in a mother’s writing, hold family history. 👵🏼

[For more on Armenian food and the diaspora, listen to this podcast episode with Liana Aghajanian.]

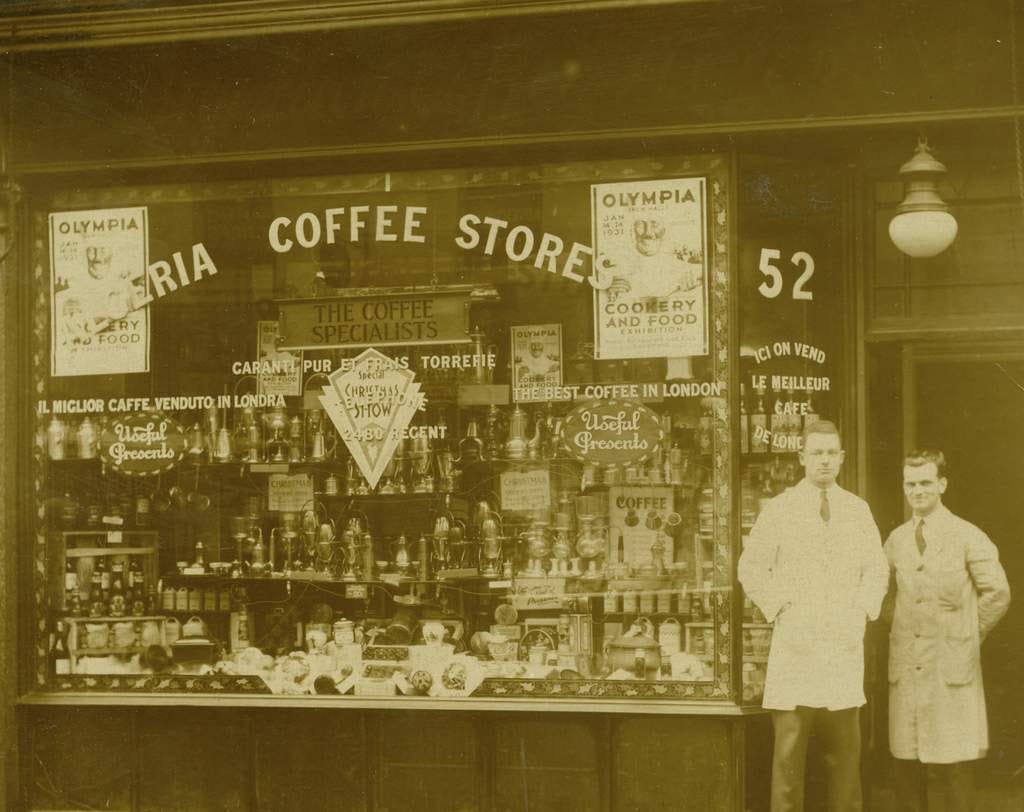

Photo: Algerian Coffee Stores

A Soho Century at Algerian Coffee Stores

By Valorie Clark

On Old Compton Street in the heart of Soho resides the oldest coffee shop in London: Algerian Coffee Stores. It was opened in 1887 by a man remembered only as Mr. Hassan, an Algerian immigrant to London.

When Hassan set up shop, Soho wasn’t the fashionable district Londoners know today. It was a seedy place where sex workers operated at all hours and gambling dens were so prolific that the nascent Metropolitan Police Force gave up on keeping them in check. When I spoke with Marisa Crocetta, the woman who runs Algerian Coffee Stores today, she laughed that Soho’s history is full of “different kinds of partying” than the clubs and upscale bars present today.

In the 19th century, immigrants were pushed out of central London by the England-born wealthy elites who had convinced themselves that the crime wave London was experiencing was an import, brought to London alongside different languages and new-to-them coffee. Soho and the West End were the fringes of the city then, and Charles Booth’s London records a borough where the police were more concerned with making sure petty crime didn’t escalate into violence (and accepting bribes) than with cracking down on lucrative vices. On the border with “respectable” London, where theaters were cropping up, men used nearby Hyde Park to meet for secluded trysts. Of course, the same Londoners who pushed out the immigrant families could easily cross over and sample the “lower class” culture, then retreat to their homes.

For a century, Soho was considered London’s French Quarter because of how many French immigrants had settled there. They opened shops, bars, restaurants, and French-style brothels. Photos of Old Compton Street in the 1880s show exclusively French language advertisements in the windows. This is probably how Mr. Hassan came to land in Soho, selling coffee imported from Africa: After France conquered and annexed Algeria, Algerian immigrants were treated as French.

Into the late 20th century, the street was still dominated by independently-owned establishments. Crocetta, whose family has owned ACS since 1946, remembers how those independently owned places disappeared one by one. “Now it’s really trendy eateries and bars, places to hang out, places to be seen.” (Bars look independent, but are in truth owned by restaurant groups.)

In the midst of that see-and-be-seen atmosphere, the coffee store still exists, and still looks much the same as it did when Mr. Hassan originally opened the doors. It feels like a confectionery - a candy-striper red and white awning greets guests, and the roasted and raw coffee beans are packaged into bright red bags. Most of the shop’s revenue comes from selling beans, but visitors can also get a cappuccino for £1.20.

“There’s never a dull moment,” Crocetta says. Action for 130 years - no reason why it should stop now. ☕️

This newsletter is edited by Katherine Spiers, host of the podcast Smart Mouth.

Instagram | Twitter | Facebook

A TableCakes Production