If you haven’t become a paid subscriber yet, please consider it. The money goes straight to paying freelancers a good rate - much better than most publications. And if not that, click on the heart icon above so I know you’re reading!

The Menu del Día: Culinary Remnant of the Franco Era

By Robert Cassidy

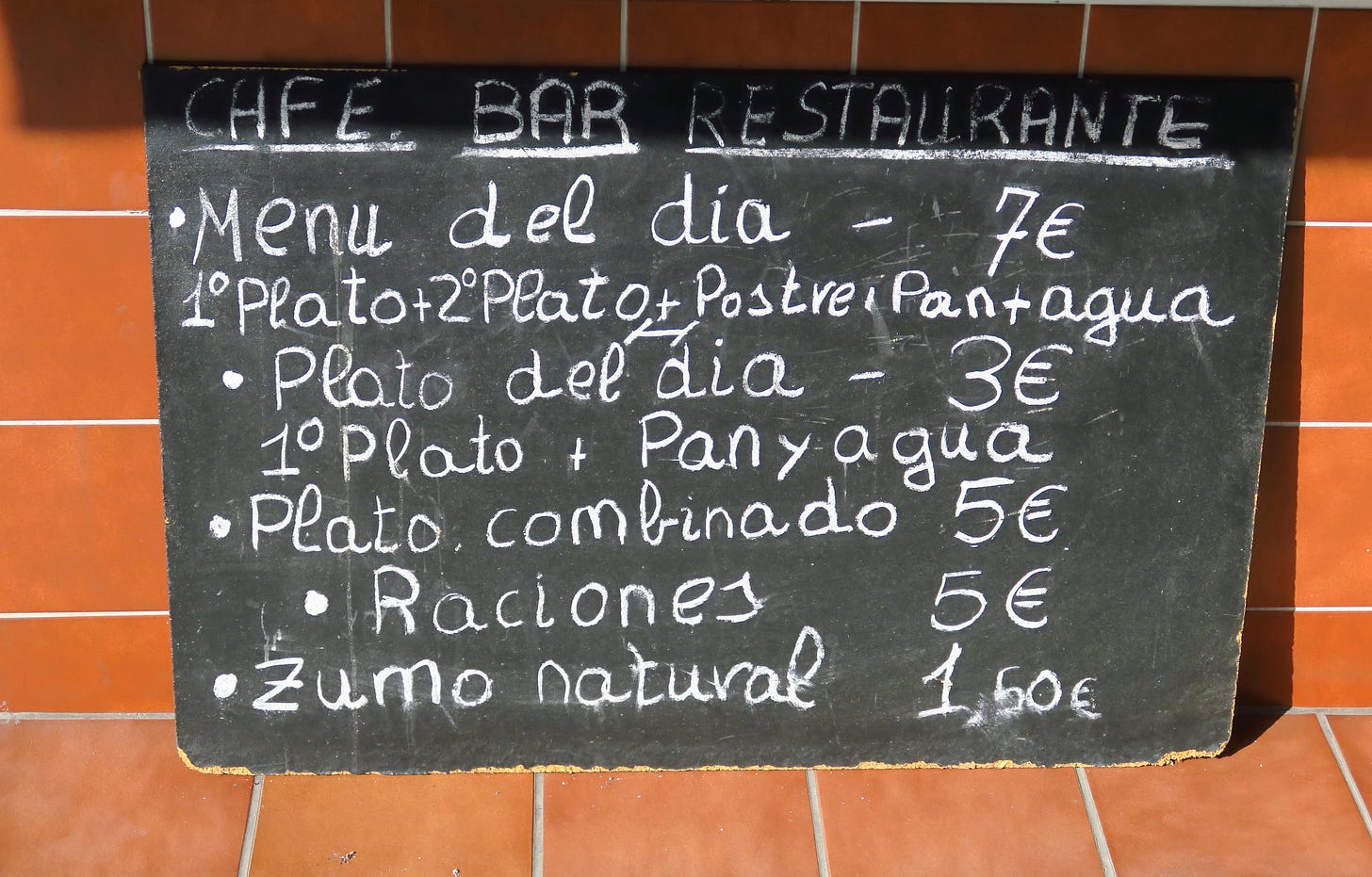

Starting at about 1pm on weekdays, restaurants all over Spain put out chalkboards with the same, hand-scrawled phrase: Menu del Día. The menu del día, or menu of the day, offers what, at least to visitors of the country, may seem like an impossible bargain. For a price often in the 8-14 euro range, customers of even high-end restaurants can access a fixed menu consisting of a soup or salad course and an entree-sized dish, accompanied by fresh bread, wine or beer, and a choice of coffee or dessert to finish everything off.

Menu del día plates favor seasonal and local specialties. Vibrant pistos and tender solomillos are classic main courses, with rich flans and rice puddings common for dessert. Although some foreigners might find such an elaborate lunch to be a bit extreme, lunch is the most important meal of the day in Spain, so vital to the food culture that is often referred to simply as la comida, or, “the meal.”

But what isn’t explained by a country’s simple love for lunch is the price tag. Mid-day meals bear a similar weight in France and other European countries, after all, but one will be hard pressed to find a menu du jour that matches the price and size of the Spanish equivalent. While many believe that the menu de día is simply a meal marketed to workers without the time to return home for lunch, the modern form of the menu del día actually dates back to 1964, to a Spain still living under Francisco Franco’s oppressive dictatorship.

By this time, Franco had been in control of the government since his faction’s victory in the civil war in 1939, but had thus far failed to find a path to economic recovery following the conflict. With liberalizing economic and cultural reforms in the 1950s, Franco’s government aimed to capitalize on a growing international tourism economy. Adopting cheery slogans like “Spain is different,” Franco’s ministry of tourism sought to market the country as a cheap destination for beachy, sunny tourism. In the summer of 1964, the government mandated that all restaurants offer a menu turistico, requiring clear advertising and the inclusion of “appetizers, a soup or cream first course, a second course of meat, fish or egg with sides; a dessert with fruit, a sweet or cheese; bread, and a quarter liter of local wine, beer, sangria or other beverage” at prices set by the government.

But while this mandate gave the menu the form that it still holds today, it was not always so popular. Under the initial policy, restaurant owners were not allowed to offer any other lunch menu besides the menu turistico, and many found it so difficult to make a profit at the government-regulated prices that early menus tended made from low quality ingredients, with restaurant owners and waiters discouraging their clientele from ordering them.

Even after a shift to slightly more flexible pricing in 1965, the portions being served were of such meager size and quality that journalists quipped that trying to subsist on menu turisticos would result in starvation. Food critics would later claim that this period led to a general degradation of Spanish cuisine for the sake of attracting mass tourism. Even the cheaper restaurants had tended to serve authentic cuisine before the legislation, but were forced to abandon traditional cooking in order to cater to international visitors with shrimp cocktails and shabby paellas.

By 1970, the term “menu del día” was introduced in new legislation, and restaurants could serve other food alongside the menu turistico, with a priority placed on regional specialties. Prices were raised marginally again in 1976, but it was not until 1981, years after the end of the Franco regime, that the mandatory prices were removed and restaurant owners were allowed the economic flexibility to be more creative with the lunchtime deals. Since then, the menu del día has risen in price, quality and popularity.

In 2010, the federal requirement for a menu del día offering was finally removed and the legislation of tourism was delegated to the regional governments of Spain’s autonomous communities. Today, Madrid is the only community where the original 1965 decree remains in place, but the menu del día is still alive and well in every corner of Spain. 🇪🇸

More Food Media:

I found a very cool chocolate cooperative.

A story from 1948 about a very strange case of food poisoning.

I had no idea vending machines had been around so long.

Episode 212: History of NYC Restaurants with Nikita Richardson

A nation once obsessed with celery; Nikita groups foods like friends.

Listen to Smart Mouth: iTunes • Google Podcasts • Stitcher • Spotify • RadioPublic • TuneIn • Libsyn

If you liked the newsletter today, please forward it to someone who’d enjoy it, and tap the heart icon above or below, which will help me reach more readers. I appreciate your help, y’all!

This newsletter is edited by Katherine Spiers, host of the podcast Smart Mouth.

A TableCakes Production.

Want to contribute? Here are the submission guidelines.

When I lived in Madrid, 20 years ago, I practically subsisted on menu del dia. My favorite place in my neighborhood, Chueca, was La Nieta, which was a very traditional Spanish working man's place, homey and inexpensive. Thanks for a great piece.