If you enjoy the newsletter today, please forward it to someone who’d enjoy it, and tap the heart icon above, which will help me reach more readers. I appreciate your help, y’all!

This is the free edition of Smart Mouth. If you like it, consider a paid subscription. *If you would like to give less than $5, you can do that via Patreon, and it is very helpful and appreciated!

From Fish to Mushrooms to Tomatoes

When most people in the western world think of ketchup, what comes to mind is a thick, savory/sweet tomato sauce. But our current ketchup is just the latest iteration of an ever-evolving condiment, which began as fish sauce, morphed into a savory mushroom sauce, and finally became the tomato condiment we know today.

So how did we make the shift from fish to tomatoes?

In the 1600s and 1700s, English colonial traders began importing fish sauce from the Asian continent (some sources say from China, others from Southeast Asia), and the umami-rich condiment piqued English diners’ interest. It also coincided with a time when English relationships to sauces where in flux: British culinary historian C. Anne Wilson says that the seventeenth century saw a proliferation of thin, uncooked sauces like verjuice or citrus juice, sometimes combined with herbs, spices, or capers. Imported fish sauce (though technically a “cooked” sauce) was on the menu too, adding salt and savory depth to dishes.

But the raw sauce obsession was short-lived, as changes in dietary recommendations and culinary trends shifted away from sauced meats and towards pickles served alongside meat: A heartier, toothsome condiment rather than simply a dressing.

The simple sauces went away, but the English desire for salty umami didn’t, and pickled condiments bridged the gap between contemporary food trends and a longing for flavor-packed sauces.

While pickles were nothing new in England, in this moment we see a shift away from a simple pickle and towards a pickle informed by burgeoning international trade: These pickles featured a hefty helping of spices, including allspice and black pepper, which we still see in today’s ketchup recipes.

The pickles themselves were made from all kinds of things including walnuts, herbs, and most notably, mushrooms.

When mushrooms are salted and allowed to sit, then pickled with vinegar, they form a dark, rich sauce, and soon enough this creation was as sought-after as the mushrooms themselves.

The umami-rich condiment was vaguely reminiscent of the imported fish sauces, and the name “ketchup” is thought to be a heavily Anglicized version of the Hokkien Chinese word, kê-tsiap, and the word was applied broadly: By the mid-1700s, mushroom ketchup, fish ketchup, and walnut ketchup were all in regular rotation.

Of these three broad ketchup types, the mushroom was most popular, and the earliest known recipe appears in 1728. However, it was also common to blend ketchups, and these blends (often mushroom and walnut, sometimes also with anchovies) became the predecessor to Worchestershire sauce.

By the mid-1700s, many cookery books and manuscripts include at least one ketchup recipe, but at the dawn of the next century, the winds of change began to blow again.

In 1804, James Mease’s “Domestic Encyclopedia” noted that “love apples” (tomatoes) make “a fine catsup,” and Mease later published the first known tomato ketchup recipe in 1812. His recipe used unstrained tomato pulp along with the usual ketchup spices, making for a thicker result than its fungal forebear.

But mushroom ketchup’s popularity reigned supreme through the Victorian period, and it took nearly a century of time and an ocean of distance to topple the condiment from its throne.

1876, Henry J. Heinz began making ketchup and sold it at the Philadelphia World’s Fair. While he was not the first to bottle ketchup commercially (nor the first to make tomato ketchup), he was the first one to make tomato ketchup a large-scale commercial enterprise.

The production process for his ketchup was faster and more streamlined than mushroom ketchup (tomato ketchup is simply simmered, while mushroom ketchup is fermented overnight and then cooked), making it easier to scale up to a commercial level. American ketchup also included sugar (and a good amount of it), changing the profile to sweet and savory.

Heinz’ skill as a salesman paid off, and the American public was enamored with his ketchup. To this day, most every American household has a bottle of ketchup in the fridge. However, the same is not true of Britain: While ketchup is a popular enough condiment, Jon Langford says that Brits see potatoes as a blank canvas, upon which can be painted a whole range of flavors.

He also notes that Heinz’ ketchup came about as America’s national palate was emerging, perhaps nudging us towards our national love of sweet-and-savory. Though mushroom ketchup itself may not grace every table, its legacy does: By the time Heinz exported to Britain, he was up against centuries of savory sauce history, and his ketchup (though popular) never could entirely displace the British desire for savory condiments with salty food. 🍅

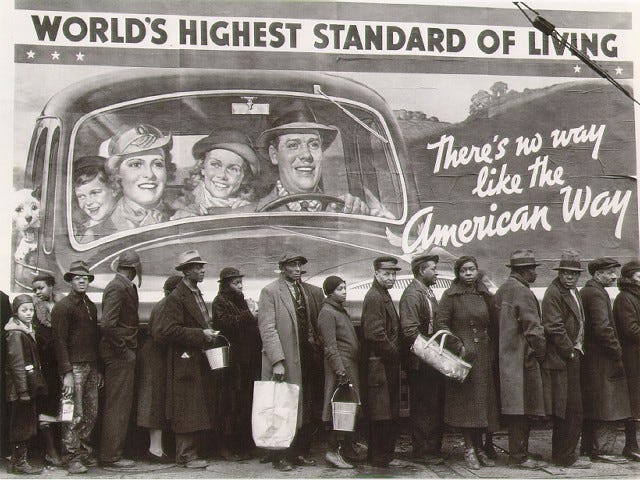

Breadlines and Famines with Jeremy Bowditch

Breadlines: invented in the US. (Truly! By a yeast company.)

Famine: always manmade, always political.

Consider signing up for a paid subscription. The money goes toward paying our contributors around the world and, starting in March, a special extra edition every month. (If you like, you can choose any amount over $5 in the “supporter subscription plan” field.)

*If you would like to give less than $5, you can do that via Patreon, and it is very helpful and appreciated! You can give just $1/month, and you’ll get podcast episodes early.

This newsletter is edited by Katherine Spiers, host of the podcast Smart Mouth.

A TableCakes Production.

Want to contribute? Here are the submission guidelines.