Please help support independent journalism! This newsletter is delivered to everyone who signs up for the free version. But, if you want to contribute financially, that would be wonderful. Substack sets the minimum at $5/month, so you can't give less than that,* but please feel absolutely free to give more.

Thank you for your support!

*If you would like to give less than $5, you can do that via Patreon, and it is very helpful and appreciated!

Are we connected elsewhere? Say hi on: Instagram | Twitter | Facebook

Please forward Smart Mouth to someone who likes reading about foodways and culture!

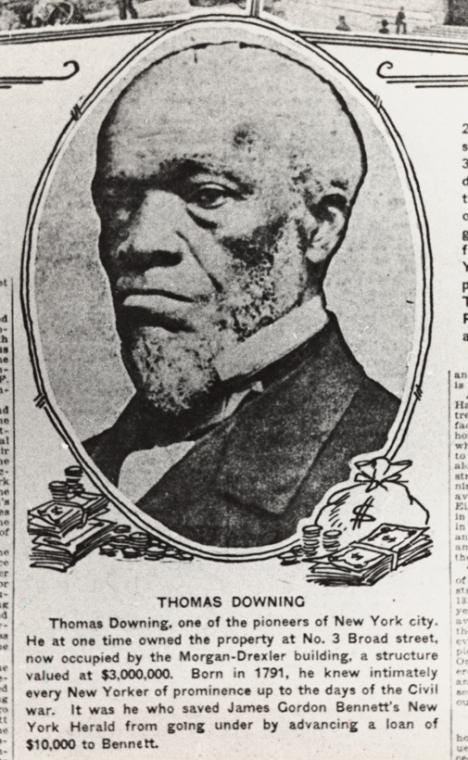

Image: NYPL Digital Collections

The Oysterman With a Vision

Today, oysters are symbols of opulence: served on the half shell, nestled on a bed of ice atop a glistening bar, brought to a table decked out in white linen tablecloths with wine glasses and gleaming silverware.

However, that wasn’t always the case in North America. In the colonial era, oysters were considered common, due to their abundance and affordability, and were often served with alcohol at oyster “refractories” or “cellars,” the equivalent of a modern-day bar. In New York City in the early 1800s, these establishments made up almost half of the restaurants in the city and were considered an unsavory place for men and women of taste to visit. However, a free Black man changed the perception of oysters, and oyster restaurants: under his direction, to one of refinement, elegance, and status.

Thomas Downing was born in Chincoteague, Virginia in the 1790s. During his youth, he spent much of his time reaping the bounty of the fertile Chesapeake Bay by fishing, harvesting for oysters, digging for clams, and catching terrapins.

After moving north and finally making his way to New York, Downing became an oysterman, and opened his own oyster house close to the New York Stock Exchange, which gave him proximity to a wealthy clientele. In contrast to the dingy and musty oyster cellars of the day, he created a decadent interior with a menu to match: scalloped oysters, oyster pie, fish with oyster sauce and poultry stuffed with oysters, to name a few.

Downing’s idea paid off, and he expanded his culinary footprint into two adjacent buildings; his oysters were shipped to Paris and London, and Queen Victoria sent him a gold watch as a thank you for the oysters he sent.

However, his most profound contribution to society was using his restaurant’s basement as a stop on the Underground Railroad. While wealthy white patrons dined in the restaurant above, the below-ground cellar was a way station for “runaway slaves” on their journey north.

When Downing died in 1866, the New York City Chamber of Commerce, as a sign of respect, closed for the day. Downing’s vision of opulence, grandeur, and innovative oyster dishes ensured that his legacy lives on in American culinary consciousness each time oysters are served with champagne. 🦪

More Food Stories

“It's time to pivot Canada's food system into the 21st century.” Well, all right! Let’s do every country, while we’re at it.

On Montana Public Radio, Sarah Aronson interviews Stella Fong, who wrote a cookbook called Flavors Under the Big Sky. It’s an extremely public radio interview and it’s very soothing to hear their gentle exclamations about wild asparagus.

Kitchen Arts & Letters is a great cookbook store in NYC, and one of the owners wrote a little piece about the kinds of books the store does NOT carry. I mean … it’s a little spicy.

This newsletter is edited by Katherine Spiers, host of the podcast Smart Mouth.

A TableCakes Production.

Want to contribute? Here are the submission guidelines.