This newsletter has a bonkers high open rate, which is very exciting to me and my homegirls (freelancers). If you haven’t become a paid subscriber yet, please do!

Did you have a favorite school lunch offering? Comment below.

(The audio version of this story is here.)

School-provided lunches have existed in the US for about 130 years, if you count the early days when private welfare groups handled the gig. School lunches have never been paused since they started, but the impetus for providing them has varied widely.

Meals provided by day schools was a concept that followed shortly after compulsory education was implemented in most states. Those two facts aren’t officially related, but we’ve got to imagine that if every child is in school, adults would notice how many were hungry. The physical way school lunch systems were set up was copied directly from cafeterias, which were first set up near factories. And schools were designed to look like and operate like factories: so, the emergent factory system, the institutionalization of public education, and feeding people in a line are also closely related concepts.

Breadlines and Famines with Jeremy Bowditch

That makes it sound like school lunches were a nefarious invention. I actually think the origins of the US school lunch is entirely noble. But it did, of course, turn ugly pretty quickly.

Various welfare groups in the late 1800s became interested in nutrition, especially children’s nutrition. These groups would have all considered themselves progressive - after all, 1896-1916 is known as the Progressive Era - though of course definitions change, and some things that were considered, well, woke, back then certainly are not now.

When public schools were first set up in the US, it was expected that most students would go home for lunch - or in the bigger cities, get lunch from a cart. (And I bet there are listeners right now who had that experience - it was pretty common into the 1970s.) Of course, not all students had the same resources, so plenty of kids weren’t actually eating food during the lunch break.

This came to the attention of various women-led charitable groups. Women’s groups were becoming more and more political, and active in the public sphere, at this point. Many of them were created as part of the temperance movement. (Side note: I was taught that women like Carrie Nation were crazed prohibitionists, and maybe they were, but the women calling for temperance were doing so because they’d notice that when husbands got drunk they were more likely to beat the shit out of their wives. When you think about it that way, the whole movement really makes a lot more sense.)

As best we can tell, school lunches - SORT OF as we know them - started in 1894 in both Philadelphia and Boston. They were low-cost and funded by private organizations, and were intended to provide a nutrition curriculum along with the food. People didn’t really care about that part, so the “feeding kids” element became the main selling point.

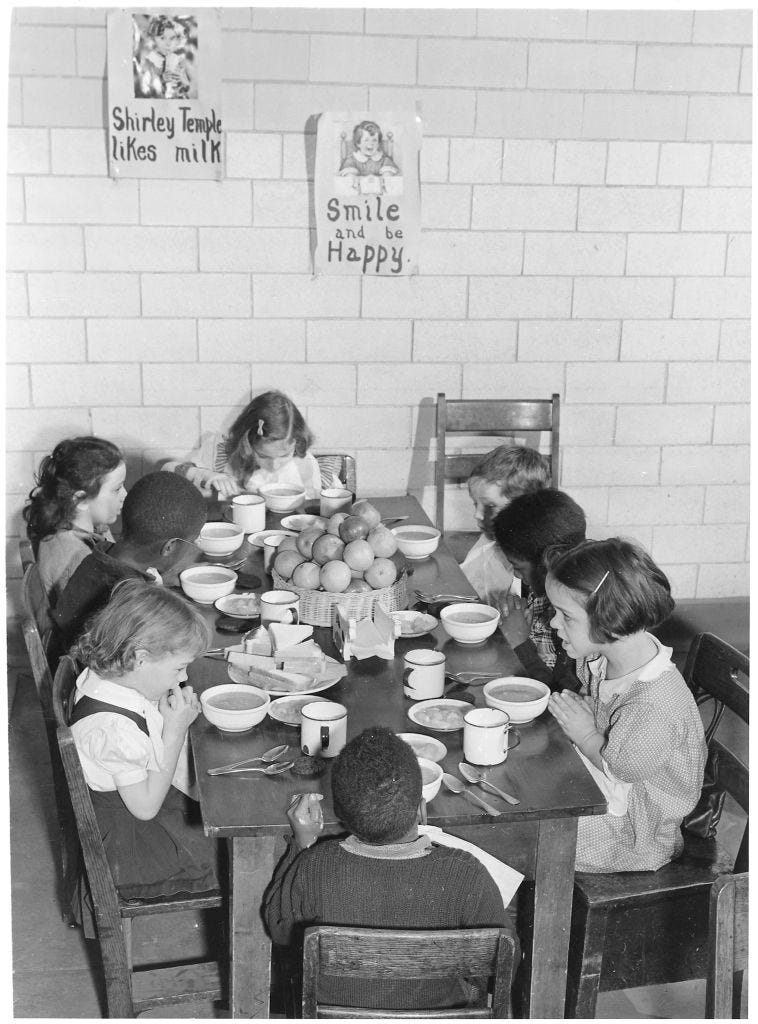

The lunch programs mainly operated in poor, immigrant neighborhoods. In New York City especially, meals were catered to the student demographics - majority Italian schools got Italian food, Jewish kids got Ashkenazi food, Irish kids got Irish food. The idea was to make them comfortable. Generally speaking, kids paid about two cents for a bowl of stew and one cent for a dessert. This private system lasted more or less through WWI.

But when the government got involved, everything flipped. The powers that be now wanted children to eat “American” food. Their reasons were war-related: they felt new immigrants would feel more American if they ate “American” food, and they wanted kids getting enough calories to make them grow up to be strong soldiers. For the next war that they knew was coming soon, and any after. As Jane Ziegelman put it in her book 97 Orchard, “the Board of Education looked to the school lunchroom to Americanize the immigrant palate."

Apparently, out of all the European immigrant groups, it was most difficult to get Italian children to eat “American” food. This makes sense to me.

A darker note: these immigrant kids were taught that their food was weird, in contrast to cafeteria food, which they were told was “normal.” It was also expected that children would return home to inform their parents about “American” meals and food hygiene.

By 1917 high schoolers were told that they should consume 800 calories for lunch. (Another world, when people were taught to aim for a high number, rather than focusing on reducing.) Menus were often posted with both prices and calories - again, the calories presented in direct opposition to why they’re presented now.

Here’s an excerpt of a menu from the late 1910s:

Veal stew with vegetables, bread and butter...Calories: 350; Price, 10 cents

Chopped egg sandwich...Calories: 200; Price, 4 cents

Bread pudding, chocolate sauce...Calories: 275; Price, 4 cents

Now we’ve reached a point where the federal government is interested in feeding children, in the service of nationalism and war preparedness. (In WWI malnourishment was the leading reason aspiring volunteer soldiers were rejected.) And then, the Depression hit. And the government looked for ways to keep farmers afloat. They scanned for options and saw school lunches and a million light bulbs popped.

The Federal Surplus Commodities Corporation was created in the 1930s as part of the New Deal. Its stated goal was diverting agricultural surpluses away from the market by giving them to food banks and other relief organizations. The intention was to keep market prices artificially inflated while also making sure poor people ate - an idea came to after a 1933 artificial-inflation plan of plowing crops under and killing six million pigs and throwing away the carcasses was not received well by the public. The Corporation’s initial contribution to school lunches was the subsidization of milk, making it more affordable to the programs that brought food to schools.

School lunches were now beneficial in two ways: feeding children and paying farmers. And the conservatives of the 1930s were entirely supportive of the idea - because they thought well-fed kids would both enjoy fighting wars and be resistant to socialism. (Free lunches are a socialist program, but politician logic is different from our own.)

FDR took one additional action with regards to school lunches that probably didn’t seem like a huge deal, but I think changed the entire course of US culture. Certainly its culinary history.

Roosevelt hired the anthropologist Margaret Mead to head the emergent federal school lunch program. Mead is probably most famous for her 1928 book “Coming of Age in Samoa” and her later research into sexuality in Pacific Islanders. After all, that’s way more titillating than school lunches, and it is believed to have influenced the so-called sexual revolution of the 1960s. But it’s her work with the National Research Council's Committee on Food Habits that, I propose, had the biggest impact.

Mead believed that all children should eat. This is reasonable. She believed that they all should get to eat the same food - this seems pretty reasonable, too! At first glance. But her method of getting the same food to all kids was, essentially, to take food down to its lowest common denominator. That meant making food as monotone and bland as possible. It meant purposefully eliminating as many seasonings as possible: truly, it was recommended that only salt be used. Since the food was to be mass-produced, there was no hope of it being high-quality. These two elements right here, I believe, combine to create the origin of the “white people food is bland” idea. No seasonings and low-quality ingredients? Yeah, that’s going to make for bland food. But this was the goal.

So we have this moment in the late 1930s to early 1940s where, though the food was not interesting, school lunches existed to feed children - the reasons for making sure they got enough calories were pretty suspect, but the end goal was pure: giving kids meat, beans, green and yellow vegetables, citrus, milk, bread, and butter. (This food lineup was a huge deal in mid-century US culture. It’s in the Betty Crocker cookbooks, too.)

But then! In 1943, farm surpluses started drying up. This sounds like a good thing - people could afford to buy food again! But, free market prices were not as profitable as those offered by the government. So farmers lobbied Congress and got them to approve $50 million to give to school boards, earmarked for buying surplus crops. This sounds like a joke, but it’s true: school cafeterias were absolutely overrun with canned stewed prunes. Various consumer groups complained, and the federal Office of Education was given a few million dollars to oversee distribution .. and the USDA was given another $50 million. (The Department of Agriculture has, as long as school lunches were a federal program, been in charge of them - education commissions have tried and failed to take control.)

A 1958 LA Times article described the surpluses the local school district received the year before: 459,662 pounds of ground beef and stew meat, 222,646 pounds of loaf cheese, 74,304 pounds of cheddar cheese, 72,996 pounds of pork luncheon meat, 90,000 pounds of lard, 146,500 dozen eggs and 154,000 turkeys. Lunches in elementary schools at that time cost 25 cents.

School lunches operated for the next 20 years in much the same fashion: buy up surpluses, get calories in kids. But then in the late 1970s this interesting new angle popped up. Some thought leaders started arguing that school lunches … were causing obesity. Folks, sometimes it’s hard to see the conspiracies right in front of us, but we can spot them pretty quickly when they occurred 40 years ago. School lunches are causing obesity? Guess we better make them smaller and use bad ingredients! Especially galling is that the same people saying school lunches had too much fat also said the students were throwing away too much food. And finally … in its report to Congress arguing for diminishing the school lunch program, the Comptroller General of the United States stated that it didn’t have any proof about kids getting fat or throwing away their lunches. No proof!

I think our first instinct is to think “well of course no one’s going to publicly oppose feeding children.” But then you remember Republicans and you’re like, “ohhhhh, right.” In 1981, Ronald Reagan’s administration cut the school lunch program by $1.5 billion, reduced serving sizes, and, pretty famously, classified ketchup and relish and vegetables. The subsidies were reduced too, which raised prices for students. (To be fair, noted Republican Richard Nixon had actually expanded the National School Lunch Program during his tenure. That guy really contained multitudes.)

The ketchup thing drew such outrage that Reagan canceled it, it must be noted - he said, and again I am not joking, that some Democrat must’ve added that line as an act of sabotage.

The overall budget cuts remained, however. This forced school districts to find ways to save money, or even make money. Hence vending machines. Hence food service companies taking over the cafeterias and serving prison food. At first, these endeavors were seen as positive by progressives, because Reagan had gutted school lunch funds so deeply that anything was worth a shot. And now, school cafeterias are a highly desirable marketplace. Nutrition has gone out the window in favor of profit, even in this, the country’s largest children’s welfare initiative.

The latest big movement in school lunches is making them free to all students - California is leading the charge on that, but of course we’ve all read the articles about school boards around the country refusing to do so, saying it would make children lazy if they didn’t have to pay to eat. I suspect real change would require the country, as a whole, to change its view toward children. In the meantime, let’s go out there and be kind to people who don’t earn enough money to pay taxes.

Sources:

National Education Association

US Government Accountability Office (PDF)

School Lunch Politics: The Surprising History of America's Favorite Welfare Program

97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement

Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet

Paradox of Plenty: A Social History of Eating in America

If you enjoy the newsletter today, please forward it to someone who’d enjoy it, and tap the heart icon above or below, which will help me reach more readers. I appreciate your help, y’all!

This newsletter is edited by Katherine Spiers, host of the podcast Smart Mouth.

A TableCakes Production.

Want to contribute? Here are the submission guidelines.

Great writeup. Growing up in the 90's the kids in my high school who qualified for free or reduced lunch could get a decent meal for $.50. It was probably their only hot meal of the day (my high school was in a working class area in the Midwest). In the DC area, where I live, I'm just wondering how the pandemic has wrecked nutrition for students whose families depended on the school lunch. Maybe you can get Dan Giusti on the show to talk about school lunches.

This was FASCINATING. My favorite piece.