If you enjoy the newsletter today, please forward it to someone who’d enjoy it, and tap the heart icon above, which will help me reach more readers. Thank you to everyone’s who’s been doing that, you’re absolute angels. Also consider signing up for a paid subscription. The money goes toward paying our contributors around the world. Substack sets the minimum at $5/month, so you can't give less than that,* but please feel absolutely free to give more. (You can choose any amount in the “supporter subscription plan” field.)

*If you would like to give less than $5, you can do that via Patreon, and it is very helpful and appreciated! You will get podcast episodes one week early, and it only costs 25 cents per.

Do you enjoy eggnog without alcohol? Plus, peach schnapps trauma, a detour through Television Without Pity, and Her Majesty's Milk Punch.

You can listen to Smart Mouth on iTunes, on RadioPublic, on Spotify - or any other podcast player!

Photo: simpleinsomnia / Flickr

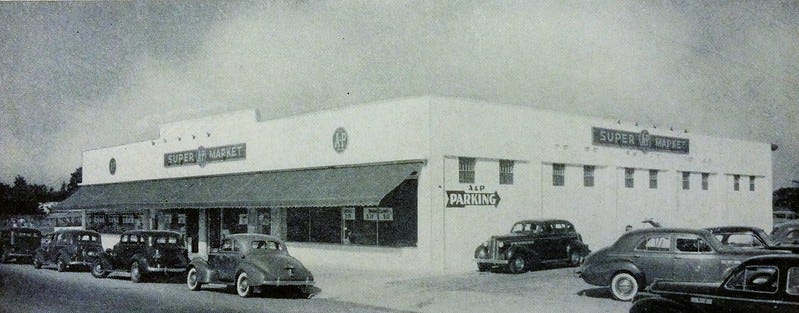

American History via Grocery Stores

By Amy Halloran

Groceteria.com is a mapping project that traces the history of supermarkets and grocery stores in the United States and Canada. Not every square foot of food shopping history is covered, but luckily for me, the ever-expanding project already includes Troy, New York, where I live. I can see that the Turkish restaurant I love was once an A&P.

The space is corner-store small, around 1000 square feet, fitting the A&P Economy Store model that began in 1912, and, says site author David Gwynn, “relied on severe cost-cutting, standardization of layout, and the elimination of credit accounts and delivery.” According to a Google sheet full of addresses on the site, sixteen A&P’s served the people of Troy from 1925 to 1940. Across the river, Grand Unions hopscotched around the edges of downtown Cohoes, skirting high rents and avoiding long leases. Some of these stores were miraculous self-service places, while others were more old-fashioned models where clerks gathered food for you, from your list.

Gwynn’s meticulous tracking of grocery stores began as a fascination for mid-century retail structures, especially the bold arches of Safeways that still dotted California cityscapes when he got there in 1992.

“Now, I’m more interested in buildings from the 1940s-50s as supermarkets evolved,” says Gwynn. He’s curious about this transition period, as chains were closing little neighborhood stores and opening supermarkets, sometimes converting a stretch of existing storefronts, rather than building a brand new store. But it’s not just architectural documentation he’s after anymore: the project has become an inquiry into how cities developed, studied through the lens of how people bought food.

Photo: Phillip Pessar / Flickr

This hobby website, begun in 1999, led to his pursuing a Masters of Library Science. Gwynn is now associate professor and digitization coordinator at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, yet his Groceteria work is cited more often than any of his academic work may ever be.

The primary resource he uses is city directories, precursors to phone books that are sturdy records of residents and businesses in cities from the 1800s forward. Big cities stopped publishing city directories in the 1930s, so he can’t trace the food retail patterns in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, or Los Angeles. But Detroit and Toronto are goldmines. Phone books, he notes, are unreliable sources.

Take a look at all the material Gwynn’s collected: historic images, chain histories, and muse about the many competing and evolving channels of food distribution that let earlier residents of your locale fill their pantries and fridges. This is a food wandering well-suited to our stay-at-home times. 🥫

Photo: Brent Hofacker

Soul Food: An American Tradition

By Azia Bradshaw

Almost every week, my mother would put together a nice Sunday dinner. She’d always refer to it as soul food and say that while hot dogs and burgers make for a good dinner on a Friday night, “Sundays are for soul food.” I used to comment on how old-fashioned that sounded (I still do tease her about it sometimes) but still, that saying of hers has always stuck with me.

Truthfully, there’s no consensus on what soul food actually is. Many equate it to "Southern food," which isn’t inaccurate, but some insist that it specifically refers to foods and recipes that African Americans left behind in the states of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, when large numbers of Black people moved north and west during the Great Migration.

Adrian Miller, a former member of Clinton’s White House turned soul food expert, agrees with the second group. In a 2016 interview with Epicurious, Miller said that “Unfortunately, ‘soul food’ has become shorthand for all African American cooking, but it’s really the food of the interior Deep South.” Miller also disabuses the notion that soul food and Southern food are the same. In his words, “I see Southern food as the mother cuisine - it tends to be more on the bland side, not heavily spiced.”

Arguably, the origins of soul food began during the transatlantic slave trade. During the forcible transportation, slavers exerted control by limiting food intake during the voyage. Once they reached the plantations, the control of food and caloric intake continued - in fact, slave owners seemed charitable for bothering to feed them.

Many slaves took discarded pieces of their master’s food - pig’s feet, oxtails, and the tops of beets - and supplemented them with things they’d been able to hunt, fish, or grow in their gardens. What they had to work with wasn’t exactly flavorful, so they compensated with plenty of salt, spices, sugar, and frying oil.

Most slaves couldn’t read or write, so seasoning measurements to be estimated or “felt out” on the fly; recipes they created had to be memorized and shared verbally. When the 1960s eventually came, African Americans popularized the word “soul” and from there the term “soul food” was born. The phrase was coined by Black people to honor the food their ancestors made.

The answer to “What is soul food?” is not straightforward. To some, it’s the culmination of a long, brutal, storied history that’s now a building block of United States culture. To me, however, it’s the taste of home I get every Sunday in my mom’s kitchen. 🥬

Photo: ronnybas

Ambrosia in Umbria’s Colorful Castelluccio: Lentils, ‘Mule’s Balls’ and Truffle-Laced Ricotta

By Helen Iatrou

When Italy bore the brunt of Europe’s first wave of coronavirus this spring, the tiny, isolated village of Castelluccio in Umbria came to mind. The town was wracked by an earthquake in October 2016 (the epicenter was in the nearby Perugian town of Norcia), and the crumbled stone-built homes of Castelluccio are still off-limits to residents.

Just over a year before the catastrophic temblor, I had taken a whistle-stop road trip through Umbria, Tuscany, Liguria, and Emilia-Romagna, inspired by the taste bud-taunting film “The Trip to Italy.”

The town, 109 miles northeast of Rome, was the first stop of the trip. Driving through the Piano Grande, a rambling plateau 4,764 feet above sea level flanked by the Sibillini Mountains, I felt we had stepped into a fairy tale. The borgo (hamlet) of Castelluccio di Norcia is easily spotted from afar, its traditional pastel-hued homes huddled on a hill.

Photo: Carlo Raciti

Nature lovers come here to witness an annual flowering phenomenon known as la Fiorita, which takes place sometime between late May and early July. Velvet green pastures transform into an unreal blaze of blooms: daffodils, violets, poppies, cornflowers, buttercups, and purple eugeniae.

At Il Fienile, the in-house restaurant of B&B Agriturismo Antica Cascina Brandimarte, the menu is strong on regional flavor but dishes are somewhat atypical.

Owner Maria Rita Brandimarte, who earned her kitchen chops from mamma Adua, sources ingredients from the family farm. She pairs creamy ricotta with shavings of nero Norcia, the king of truffles in these parts, and honey, for an ambrosial threesome that had me speaking in tongues.

Tagliatelle served with pancetta, asparagus, and truffle is made with flour from roveja, a wild pea cultivated here since Neolithic times. Together with fava and cicerchia beans, it served as vital sustenance for agricultural workers. Saved from extinction, the legume has been reinstated as a locally important crop.

Residents are particularly proud of their delicate, thin-skinned variety of lentil, bearing Protected Geographical Indication status, that is grown and gathered by hand.

While their hotel remains closed for repairs, the Brandimarte family supplies numerous items to La Vostra Cantina, which also operates an online shop.

You can trust the Italians to come up with cheeky names. A salami hailing from Norcia is known as coglioni di mulo (the mule's balls), named in honor of the animal’s centuries-long contribution to rural life in the Apennine Mountains.

Castelluccio’s reconstruction is scheduled to finally start in coming months.In a metaphor for people’s resilience, this year’s la Fiorita was one of the most spectacular in years, with the lentil’s purple flower proving the star of Mother Nature’s technicolor performance. 🇮🇹

This newsletter is edited by Katherine Spiers, host of the podcast Smart Mouth.

A TableCakes Production.

Want to contribute? Here are the submission guidelines.

Now I'm missing Italy more than ever! Truffle-laced ricotta?? Food of my dreams.