Are we connected elsewhere? Say hi on: Instagram | Facebook

Please forward Smart Mouth to someone who likes reading about food!

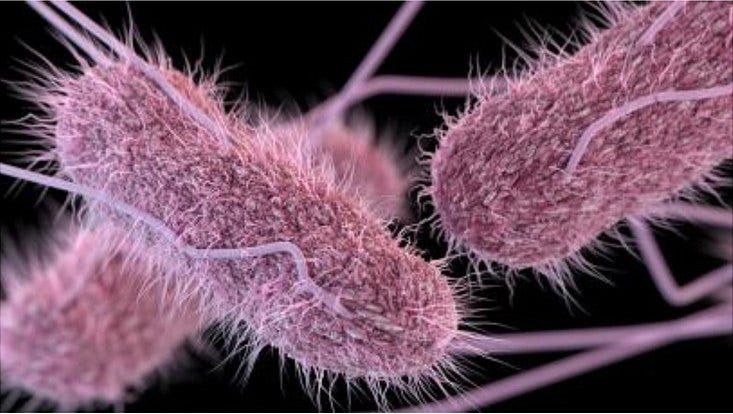

Photo: James Archer/University of Hamburg

You’re Quite Possibly Wrong About What Gave You Food Poisoning

When the news broke recently that Los Angeles restaurant and media darling Sqirl had been storing and selling moldy jam, there were a lot of comments on social media along the lines of “wow, well, I never got food poisoning there!” Maybe that’s true that no one ever, or very rarely, got sick from eating Sqirl’s jams. But there’s no way to tell now, even anecdotally: people are truly bad at identifying what gave them food poisoning.

There are a number of reasons for this, most of them based in weird and interesting science facts. For instance, diseases that can be foodborne don’t necessarily come from food. They can also be transmitted from animals, people, and water (both the swimming kind and the drinking kind). Someone’s debilitating gut bug could have come from paddling in a lake or shaking a colleague’s hand. (Sidenote: shaking hands is cancelled even if we get a vaccine, right?)

Geography also plays a part in what kind of food poisoning a person might get, and what its source is likely to be. Different foods have different likelihoods of making people sick on different continents.

“Certain food items are more commonly associated with food poisoning than others,” says a European microbiologist I emailed with who wants to stay anonymous, but who I promise knows what they’re talking about. “This varies somewhat with factors including the country, climate, animal husbandry/biosecurity and food preparation practices. For example, S. aureus is very common in the USA but rare in the UK and probably relates mainly to temperature.”

According to a study published in the International Journal of Food Microbiology, in the EU, Campylobacter outbreaks come mostly from poultry, but in the US, they’re usually traced back to dairy products. In the EU, you might get Salmonella enteritidis from eggs; in Canada E. coli is usually associated with beef. Salmonella is a problem in all English-speaking areas, but in Australia and New Zealand, Salmonella typhiumurium specifically is the most frequent offender.

The main science-based reason why people can’t always tell what made them sick, though, is the incubation periods of various foodborne illnesses. Toxins from Staphylococcus aureus, which can come from meat and basically anything creamy, like filled pastries, can hit you inside of an hour. Clostridium botulinum and Clostridium perfringens, found in improperly canned and/or heated food, can make you sick within half a day of consumption. But on the other end of the spectrum, Giardia lamblia, found in produce, will probably take at least a week to make you sick, and Hepatitis A (produce and shellfish), a month. Most of the rest of the filth will sicken a person at some point inside of a week. So while the inclination is to blame a pukefest on a burger you ate yesterday, it could just as easily be from a salad you ate five days prior.

According to my mystery biologist, “the biggest causes for gastrointestinal illness are norovirus (which is often not transmitted directly via food) and campylobacter (mostly sporadic cases rather than outbreaks, a lot transmitted from chickens which are endemically contaminated).” That means you might have been infected 12 to 48 hours ago by an unwashed hand (norovirus), or 2 to 5 days ago by meat contaminated with feces (campylobacter). Individual constitutions play a part, too. “Studying outbreaks can show a spread of onset times for people who ate the same meal.”

Another factor proven by investigations, including one in the Journal of Food Protection, is that people don’t have very good recall of the food they’ve eaten in the week prior. Even if they contemporaneously record their meals, seven days later, people have generally forgotten most of what they ate. According to my anonymous scientist, “people most commonly blame the last food they ate outside the home for food poisoning symptoms. Evidence is often lacking that they’re correct.”

More specifically, there’s a long history of white Americans blaming so-called “ethnic” restaurants for their digestive ailments. In the case of Chinese restaurants, this is baked in to the racism created around the mid-1800s by labor lobbyists threatened by Chinese immigration: the misinformation campaigns focused in particular on disease, cleanliness and eating habits. And now here we are almost 200 years later, blithely believing old racist lies about food preparation. Accordingly, Americans of many backgrounds are less likely to consider Anglo restaurants as the source of their weakened state. (Of course we’re all most unlikely to blame our own cooking.)

Sqirl is owned by a white woman, serves a largely white customer base, and offers mostly European-derived dishes. None of that means it didn’t make anyone sick. Maybe it got lucky with questionable product. We don’t know for sure: such is food poisoning. -Katherine Spiers

More Food Stories

Food Timeline has been invaluable to me in my research for the podcast. It hasn’t been updated since the founder passed away five years ago, but her family miiiiiight be open to turning it over to someone with the right intentions.

I’m really enjoying the Midwesterner newsletter, and this edition, about regional ice cream, was especially beautiful.

Lots of infuriating stuff in this op-ed by a server who’s back at work already!

This newsletter is edited by Katherine Spiers, host of the podcast Smart Mouth.

A TableCakes Production.

Want to contribute? Here are the submission guidelines.