If you enjoy the newsletter today, please forward it to someone who’d enjoy it, and tap the heart icon above, which will help me reach more readers. Substack just changed its homepage so now it’s even more important. I appreciate your help, y’all! Also consider signing up for a paid subscription. The money goes toward paying our contributors around the world. Substack sets the minimum at $5/month, so you can't give less than that,* but please feel absolutely free to give more. (You can choose any amount in the “supporter subscription plan” field.)

*If you would like to give less than $5, you can do that via Patreon, and it is very helpful and appreciated! You will get podcast episodes one week early, and it only costs 25 cents per.

Peppermint with Niccole Thurman

What is “childhood”? When was it invented? The same time as candy canes?

You can listen to Smart Mouth on iTunes, on RadioPublic, on Spotify - or any other podcast player!

The World's Best Pizza Is in Tokyo

Hypnosis occurs when you watch pizza dough stretched, in a distinct rhythm, the same way for each and every pie at SAVOY Azabujuban in the Minato ward of Tokyo. Pizzaiolo Bungo Kaneko expertly crafts each margherita, marinara and seasonal pizza to perfection, rivaling - dare I say besting - the better-known Neapolitan joints in Naples and Brooklyn.

Kaneko only makes a small number of pizzas each day, with the aim of keeping them consistent and perfect. There’s almost always a line out the door and a sold-out sign before close - he’s onto something. For the best odds of snagging one of just 13 stools, go for their weekday lunchtime special. Pizza lovers get an antipasto, peach iced tea and a choice of marinara or margherita for 1,000 yen. It’s one of the best meals under $10 in Tokyo, not to mention one of the best pizzas you’ll ever have.

The secret to Savoy’s pizza perfection might be the olive oil, or maybe it’s the salt sprinkled on top, highlighting the flavor combination of tomato sauce, garlic, oregano, mozzarella, and basil like the crescendo of a masterpiece symphony. Perhaps it’s just pure flavor hypnotism. #201 3-10-1 Motoazabu, Minato-ku, Tokyo 106-0046. 03-5770-7899. savoy.vc. -Katie Lockhart

Photo: Luxury Train Club / Flickr

Restore Train Dining to Its Former Glory

By Judy Colbert

Not long after trains started transporting people over the long miles between cities in the United States, Fred Harvey opened a chain of restaurants near the stations to feed passengers tasty, nutritious meals. Chefs were well-trained and relatively well-paid, as were the Harvey Girls who served the meals. The menus were written so that passengers wouldn’t have the same meal at every stop. The conductor and engineer would signal the restaurants to let them know how many passengers would be eating: meals would be ready for their arrival. Eventually, Harvey would own dining cars on the trains themselves.

Fast forward to the creation of Amtrak: The chefs that selected the menus were graduates of New York’s Culinary Institute of America. Railroad diners could choose from a well-marbled Black Angus steak, spice-rubbed Atlantic salmon filet, a vegetarian selection, and other entrees. Curated wines were paired with meals that were served on fine linen cloths with heavy silver-plated flatware. These repasts were a large part of the romance of the rails. The food tasted good, too - as someone who lives in the Chesapeake Bay area and is the author of the “Chesapeake Bay Crabs” cookbook, I’m leery of a menu that promotes, “lump crab meat crab cakes.” Yet, there it was on the menu as recently as 2019. It wasn’t “lump” meat, but it was tasty.

But, due to newer Amtrak management and elected officials who wanted to eliminate long-haul service to concentrate on more profitable intercity service, fine dining has ceased to exist. Dining cars were removed from the long-haul trains east of the Mississippi and replaced with café service. The pandemic gave the officials an excuse to eliminate the meals completely, so, instead of cooked-to-order meals, the trains now offer ready-to-serve “flexible” dining (in other words, meals on aluminum “plates” with plastic utensils, with a tiny salad and a roll that may or may not be heated and may or may not have a pat of butter on the side. You know, like airplane food). This is available only to passengers in sleeping cars.

User communication has come full circle. Just as hobos riding the rails left signs letting fellow travelers know where they could find work, where police were active, where towns were without booze, Amtrak passengers are now posting notes on Facebook groups. They let riders know what to order from restaurants that will deliver food to a train station when there’s a layover for a crew change or water refill. They’ll also note which stations won’t let un-ticketed people onto the station platform and if an employee at the station will accept a meal delivery and hold it for the train.

With the election of “Amtrak Joe,” there’s hope that daily service and dining cars will once again be the norm within the near future and we can look forward to fine dining on long-haul itineraries. Here’s to appreciating the journey. 🚆

Photo: Alamy

Plague Water on the Rocks, Please

Between the 14th and 17th century, plagues were remarkably common and deadly in England. The Great Plague of London (1665-66), for instance, is believed to have killed approximately 100,000 people.

In the midst of the crises emerged folk remedies, said to cure the afflicted. Hand-written recipe manuscripts and printed cookbooks were littered with techniques for concocting potent tonics with medicinal grit right alongside the custard pudding and cheesecakes. “Many of the plague cures of the day came with two sets of instructions,” writes Elaine Leong in her book, “Recipes and Everyday Knowledge: Medicine, Science and the Household in Early Modern England.” “One for prevention and another for those already infected.”

“The Queens Closet Opened,” a popular cookbook from 1655, for instance, featured a recipe for “plague water” – a heady potion made using herbs. Titled “The King’s Medicine for the Plague,” it read: “Take a little handful of Herb-grace, as much as of Sage, the like quantity of Elder leaves, as much of red Bramble leaves, stamp them altogether, and strain them through a fair linnen [sp] cloth, with a quart of white Wine, a quantity of white Wine Vinegar, and a quantity of white Ginger, mingle all together.” Its author W.M (Walter Montagu) was an English courtier at the court of Queen Henrietta Maria, wife of King Charles I. Montagu claimed that the recipes belonged to her private kitchen.

A hand-written manuscript titled English Cookery and Medicine Book (1677-1711) is preserved at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Its instructions for healing water are tucked between the recipes for pickle beans (beans immersed and preserved in vinegar; flavored with dill, long pepper and ginger) and Shrowsbury cakes (i.e. Shrewsbury biscuits, a timeless English dessert). Titled “To Make Plague Water,” the recipe asks for a blend of botanical ingredients such as agrimony (known for its curative powers), common rue, red sage, rosemary, and mugwort, to name a few. It reads: “strip and pick all your herbs, then cut them very small,” place them in a container, and then add “3 Gallons of sack or white wine and 2 quarts of Brandy.”

Why were these home-made brews laced with liquor? Certain herbs were seasonal and had a short lifespan, so they were dunked in alcohol for better shelf life and for alcohol’s antibacterial benefits.

Today, institutions like Folger are attempting to digitize these centuries-old recipes. Others have taken a different approach. For instance, University of Minnesota’s Wangensten Historical Library teamed up with the Minneapolis Institute of Art and liquor company Tattersall Distilling to create modern renditions of spirits from centuries past. Among this was the one-off creation of plague water. Ingredients like green walnuts, juniper berries, elderflower, angelica root, and mace, mixed with other herbs and spices, were used to make the artisanal drink.

While the team tried to adhere to the recipe as much as possible, certain ingredients that were unavailable were replaced with modern alternatives. Some were removed completely since they were deemed unfit for consumption: snake grass, which is mildly toxic, was substituted with licorice root. What emerged from this experiment was a crisp, bitter-tasting drink that debuted in early 2019 at Tattersall’s Cocktail Room bar.

It is highly unlikely that these waters helped prevent the spread of the disease, but today these recipes serve as historical guides, providing a rich insight into the medical and culinary practices of elite English households in the 17th century. 😷

Photo: larik_malasha

Pastry by Any Other Name

When Netflix released “Emily in Paris” in October, Parisians eagerly checked the show’s Instagram, looking for cultural misunderstandings to make fun of and be slightly offended about.

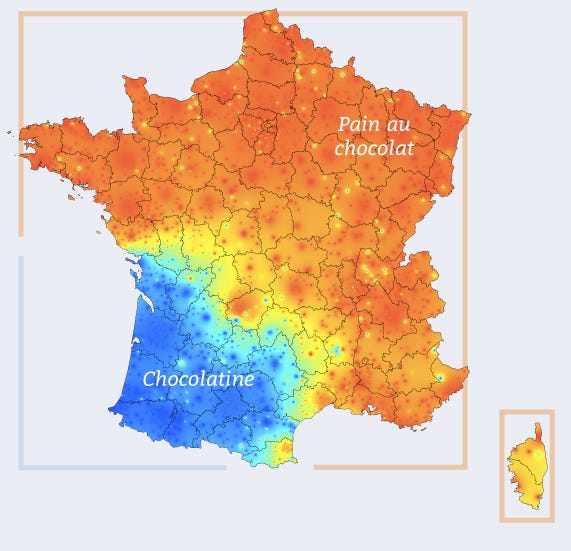

The account had posted a picture of two beloved French pastries: pain au raisin and a chocolate croissant, which it called “chocolatine.” Ask any Parisian, or 84% of all French people, and they’ll tell you there’s only one name for that pastry: pain au chocolat.

But since the early 2010s, many people from the expensive, stressful capital city have headed south to Bordeaux. To not seem like snobby Parisians, they must change their bakery ordering habits. Here in the sticks, nearly everyone says “chocolatine.”

What explains this difference?

A widespread rumor in France traces the appellation chocolatine to when the southwest of the country belonged to the English crown. English speakers would ask for “chocolate in bread,” which eventually became “chocolatine.”

Image: Adrienvh

However, the English maintained an official presence only between 1152 and 1453. Since chocolate came to Europe from the Americas, this explanation is impossible.

In 2018, 10 members of French parliament submitted an amendment to a draft law on agriculture and food to make chocolatine the official name of the pastry and “give value to the customary name and fame of a product.” The amendment said that the word has historically been rooted in the Gascon region, and is the product is the pride of all southwestern France.

The French president refused to settle the debate. His government’s actions speak louder than his apparent neutrality, however, since the minister of agriculture and most of parliament rejected the amendment.

On the international stage, some countries have picked their side. Chocolatine is the word used in French-speaking parts of Canada. Germany, Italy, the UK, and Japan have all chosen the side of pain au chocolat.

So who’s right? The food historian Jim Chevalier says that the first written mention of pain au chocolat was in 1851, when an American journalist described a small rectangular bread, made of puff pastry and filled with a slightly bitter bar of chocolate. The first mention of chocolatine in the context of pastries dates only to the 1980s.

This controversy is over-hyped, and rather than argue we should revel in how easy it is to find a delicious and comforting carb and chocolate treat anywhere in France. And at least there’s one thing we can all agree on: since the pastry is not shaped like a croissant, everyone should stop calling it a chocolate croissant. 🇫🇷

More Food Reading:

The answer is obvious as soon as you hear the question (no one expects us to buy limited-edition Oreos), but there’s some good snack information in this article.

Meditations on a Golden Girls cookbook. [h/t Stained Page News]

Tracking Christmas plans via tamale sales.

This newsletter is edited by Katherine Spiers, host of the podcast Smart Mouth.

A TableCakes Production.

Want to contribute? Here are the submission guidelines.

Ah! Next time I'm in Tokyo I must stop by SAVOY then. The pizza sounds incredible!