Are we connected elsewhere? Say hi on: Instagram | Twitter | Facebook

The restaurant industry is getting so innovative about selling product and raising money for workers. Two that caught my eye:

Erik Bruner-Yang, a chef in Washington, D.C., has launched The Power of 10, the goal of which is to pay 10 restaurant employees to make 1,000 meals weekly, paid for by donations equaling $10,000 every week. He figured it would get restaurant workers paid far quicker than a government initiative would do. The program is chugging along and has plans in the works for starting in multiple other cities. You can donate in amounts starting at $10.

The Chefs’ Warehouse usually, of course, sells to restaurants, but it’s filling and shipping orders for home use now, as are many wholesalers. This one has multiple locations across the country and is pretty high-end. It has tried to make its items more retail-sized, but that isn’t always feasible - and hey, if you were ever gonna order six pounds of baker’s chocolate or 15 pounds of bacon, now is the time. The website promises to send 10% of proceeds to “front-line furloughed employees and other impacted members of the foodservice industry,” which is rather vague. I don’t think the company is lying, but I wish they’d be more specific. The only hint I could find was this Instagram post saying the Warehouse is donating to Noshes for Nurses, a charity run by … Jill Zarin. Why not. Use the code JILLNLISA at checkout - that way at least 10%, and maybe 20%, of your money goes to a good cause.

Where are you getting groceries now? Anywhere unexpected? Let’s talk about it here.

Please forward to a food-loving friend!

Breaking Bao: The Origin and History of a Not-So-New ‘Trend’

By Su-Jit Lin

Steam rises like ghostly wisps from off-white, gently sweet half-moon buns so soft it looks like their edges are blurred. Nestled between them are glistening cuts of meat -often roasted pork belly, maybe duck - draped with a light sheen of dark sauce, ambiguously Asian in origin. Something crisp and cool to balance that richness, perhaps scallions, lightly pickled cucumbers or daikon or carrots, or maybe kimchi.

You can hardly visit an Insta-focused gastropub without seeing these pillowy handhelds on the menu anymore…but where did they come from? Are they an innovative creation of barrier-breakers fusing global cuisine?

The short answer is no.

Photo: Simon Reddy / Alamy Stock Photo

They hit the American mainstream when Eddie Huang and David Chang put them in the spotlight, but the truth is, the trendy menu item isn’t new at all. In fact, it’s super old, adapted and thrust into consciousness without too much understanding by colonizing ambassadors, as evidenced by the redundant moniker “bao buns” and its random appearances on menus with nary a trace of Chinese flavors otherwise.

The origin story of mantou, the doughy bread that lends itself to bao form, dates back to the Shu Han wars during the Three Kingdoms period in China (220 - 280 AD); its inventor was said to be the legendary politician and military strategist Zhuge Liang, a man revered as the predecessor to “Art of War” author Sun Tzu. Folklore has it that he came up with the recipe either to feed his swamp-sick troops conveniently and efficiently while on campaign in the south or, in lieu of human sacrifice, slaughtered his remaining livestock and stuffed the meat into head-shaped dough to throw into an unfordable river to appease its riled-up spirits.

Mantou became a staple starch in the wheat-growing northern regions of China and the stuffed versions became popular throughout the country under the new name of baozi, both as a large, puffy handheld for the working man’s breakfast or snack (dabao), or as steamed minis in tea rooms (xiaobao).

Making its way down south - evolving into soup-filled, sweet, and deep-fried versions along the way - mantou took what we know as its bao form in Fuzhou. Here, it was flattened into (usually) three-inch circles and folded in half then steamed, giving it the effect of having been sliced. Poetically called a lotus leaf bun (he ye bing), it becomes he ye bao with the addition of fillings, which was Taiwan’s game-changing contribution as the Fujianese made the short trip over the sea to that island.

There, it took on a life of its own as it became less common in its place of origin. The shape was so popular, it entered mass production, joining fat mantou buns in the pre-cooked freezer cases in Asian markets. And from its gua bao--red-cooked pork belly, stir-fried suan cai (pickled mustard greens), coriander, and ground peanuts--sprang not only the misconception that gua bao is Taiwanese in every respect, but every Americanized version of stuffed bao on the market today.

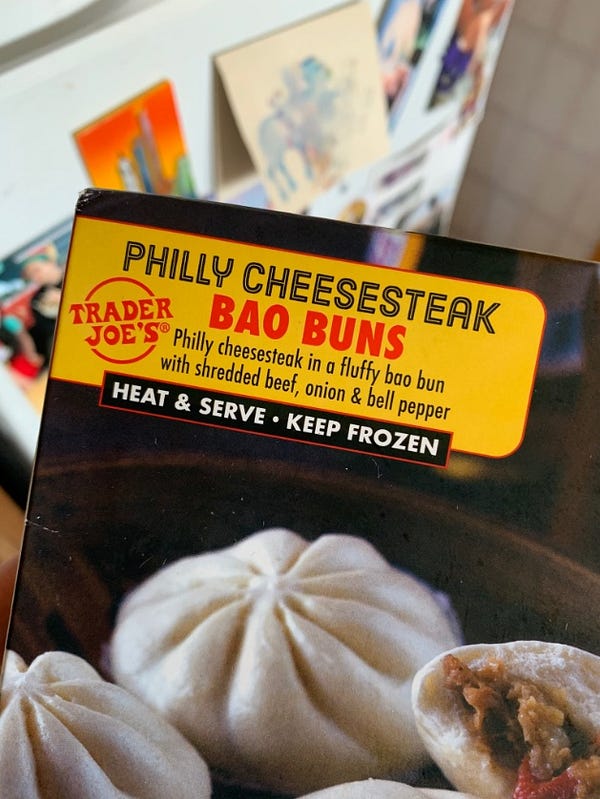

In New York, where there’s a large Fuzhou population, Peking duck is often stuffed into these sweet, pillowy layers. In other places, bulgogi makes appearances, as does katsu. Anything slathered in hoisin sauce. And you might find non-Asian flavors in there, too.

Photo: Hans Geel / Alamy Stock Photo

(But it’s important to consider the line between creativity and appropriation. Does the bao selection come out of left field, or does the menu reflect any other nods to Chinese cuisine? If the fillings are a nod to another regional or national style and borrow only the bao, are those faithfully executed and named accurately? Thoughtful execution is what separates the two.)

So innovative gourmet fare? With its humble and centuries-old history, not quite. Fresh and homemade? Even David Chang, who put a bao recipe in his 2009 cookbook, uses Peking Food’s frozen buns in his high-end restaurant. “Asian tacos” or “Chinese burgers”? Definitely not. But delicious and here to stay? With the high profit margins, mounting menu prices, and endless flavor possibilities, it’s safe to say yes to that.🥡

This newsletter is edited by Katherine Spiers, host of the podcast Smart Mouth.

A TableCakes Production.

Want to contribute to this newsletter? Here are the submission guidelines.