If You're Scared of Oysters, Maybe Blame Big Oil

This feels like the beginning of a zombie story

One of my most “will die on this hill” beliefs is that most people are incorrect about where they got food poisoning. I’ve even written about it. So of course the last time I got food poisoning I was hoist by my own petard and knew exactly when and where it occurred: eating oysters at my beloved neighborhood bistro. (The friend I was with also got sick.) (A few months later I had blood work done and my liver markers looked awful and my doctor thought I was dying, but then I remembered about the bad oysters. Doc was so relieved she laughed. Just a li’l hep A to keep things spicy.)

So, even though I have a professional interest in oysters (more on that in future editions), I am not eating them at the moment. Which, it turns out, is perfectly fine, because at least 150 people in Los Angeles have gotten sick from them in the last month - outbreaks are relatively easy to source once they get big enough.

That seems high, but over the last few decades oysters have been taking people out sort of regularly. Four people died from eating them in L.A. in May and June 1996. In November of 1982 in Louisiana, a confirmed 472 people got sick from oysters. Fifty people in Texas in December 2022. Singapore, December 2003 and January 2004: at least 305 cases.

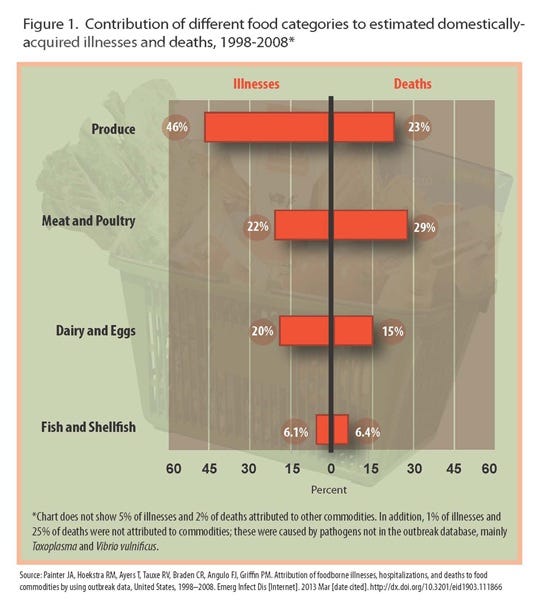

(Before I continue, let me say that I’m not trying to scare you away from oysters. The deadliest traced food poisoning outbreaks of the last 40 years have come from deli meat, fenugreek sprouts, cheese, and cantaloupe. Life is about crossing your fingers and diving in.)

Oysters can carry all sorts of bacteria and viruses, but it’s the one responsible for the 1996 Los Angeles outbreak that’s increasing most significantly. It’s called Vibrio vulnificus; it’s known to some as flesh-eating bacteria. It’s naturally occurring in brackish coastal water, and traditionally, most people caught it from being in the water with an open wound. In the U.S., V. vulnificus was once almost only found in the Gulf of Mexico, which is a relatively warm body of water, but the bacteria is believed to be spreading rapidly. This study found that “in Eastern USA between 1988 and 2018, V. vulnificus wound infections increased eightfold … and the northern case limit shifted northwards 48 km.” Those scientists think that the bacteria will be present in every eastern U.S. state by the next century.

I don’t have to tell you that this rise in bacteria is due to climate change. The Gulf of Mexico has been getting warmer, and the V. vulnificus problem was first noticed on a wider public scale in 2011. Or, one year after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

When the Ixtoc 1 oil spill happened in 1979 in the Gulf of Mexico, it was believed that its affects would only last a for few weeks after the spill finished. (Out of mind, out of water!) Humans had much more information on the topic by 2010, but not enough. For instance, it wasn’t widely known that Vibrio vulnificus loves to chow down on tar. That means the splotches of tar that roll up on Gulf beaches are potentially dangerous to a lot of people; it also means that post-Deepwater, Vibrio was getting big and strong and having lots of bacteria babies.

Oil drilling wasn’t the only man-made activity that wrecked the Gulf during the Deepwater disaster. Emergency responders were surely trying their best, but probably made everything worse. First, chemical “dispersant” was poured over the oil to break up the mass into smaller and smaller pieces until they were considered droplets, rendering it non-toxic. But the smaller the drop, the more likely it is to infest small wildlife, including oysters. In lab tests, “the addition of dispersant … led to a drastic increase in oyster death. Mortality of oysters exposed to both oil and dispersant was about 90 percent, compared to 70 percent when only oil was added.”

In an attempt to keep the oil from reaching the shore, freshwater reservoirs were opened into the Gulf. Sealife is calibrated to the saline level of the water it lives in, so when suddenly deluged with freshwater, oysters died in overwhelming numbers: between 4 and 8 billion, according to the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration. And then the shoreline was raked to physically remove oil, which led to another 8 million oysters dying. Bloop.

Surviving Gulf oysters studied from 2010 to 2013 had high levels of metaplasia — it is theorized they were able to live without feeding gills because they had adapted to “impacts from the petroleum extraction industry” over the past 100 or so years. Double bloop.

According to the CDC, confirmed Vibrio infections rose from “390 a year from the late 1990s to an average of 1,030” per year by 2016. The Gulf oyster lobby group Interstate Shellfish Sanitation Conference and the FDA know about the warm, bacteria-bubbly water and the sickly oysters, but the only solution they’ve landed on is “education aimed at high-risk groups.” Oyster farmers are already working with way fewer and much less diverse oysters than they were 15 years ago — my theory is that they know testing would show too many oysters to be unsuitable for consumption.

The FDA has also allowed the ISSC to refuse to implement post-harvest treatment such as irradiation or quick-freezing that would kill bacteria. California requires all Gulf oysters sold in the state from April 1-October 31 to be treated, a rule in place since 2003. To compare: from May 1993 to October 1995, seven people in Los Angeles County alone died of V. vulnificus. From 2003-2010, no one across California died of it; from 2013-2019, 10 did. Nationwide, about 100 people are killed by it annually.

These numbers might seem alarming, but relative to other foods in the U.S., oysters are pretty safe. It’s lettuce and spinach that most want to make you sick. Poultry aggressively wants you dead.

I don’t think eating oysters is stupid or unsafe. Letting industry run wild to the point of changing entire ecosystems sure is, though. Now bacteria are greedy for toxic, carcinogenic petroleum tar, and oysters can survive without sustenance. What comes next?

That May Not Be What Gave You Food Poisoning

Are we connected elsewhere? Say hi on: Instagram | Facebook Please forward Smart Mouth to someone who likes reading about food!

Salt the Chicken with Susan Jung

A dream job and many dream fried chicken recipes.

Listen to Smart Mouth: iTunes • Google Podcasts • Pandora • Spotify • TuneIn • Libsyn • Amazon Music

Check out all our episodes so far here. If you like, pledge a buck or two on Patreon. If you'd rather make a one-time gift, I'm on Venmo and PayPal.

If you liked the newsletter today, please forward it to someone who’d enjoy it, and tap the heart icon above or below, which will help me reach more readers. I appreciate your help, y’all!

Please note: Smart Mouth is not accepting pitches at this time.

This newsletter is edited by Katherine Spiers, host of the podcast Smart Mouth.

A TableCakes Production.

Great, thoughtful post! Thank you for being a voice of reason in an otherwise reactive, jump-to-conclusions world.

As an oyster nerd (who does oyster nerd things professionally), I wanted to help by raising a couple points of clarification. The primary vibrio that is linked to getting food-borne illness from eating raw oysters is actually a strain called Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Much harder to say, but much more prevalent, and far less life-threatening.

If you look at the FDA data, most deaths caused by Vibrio vulnificus are through exposure of open wounds and not by ingesting any food containing the pathogen. Furthermore, once you slice the data further to isolate the people who die from vibrio vulnificus via raw oysters, it's actually really, really low.

We hosted a really fascinating webinar with Robert Rheault, the Executive Director of East Coast Shellfish Growers Association and known as the "vibrio evangelist" amongst the industry to get all of the facts about vibrio and oysters. Happy to share that with you, in case if you're interested!